Control Methods for Nonlinear Systems

Nonlinear phenomena are ubiquitous in nonequilibrium systems surrounding us, such as the nervous system, fluid dynamics, meteorological phenomena, and chemical reactions.

Our research focuses mainly on developing methods to control nonlinear and high-dimensional systems, based on the theory of dynamical systems.

As an application, we are exploring methods for controlling meteorological phenomena, including the avoidance of extreme rainfall events.

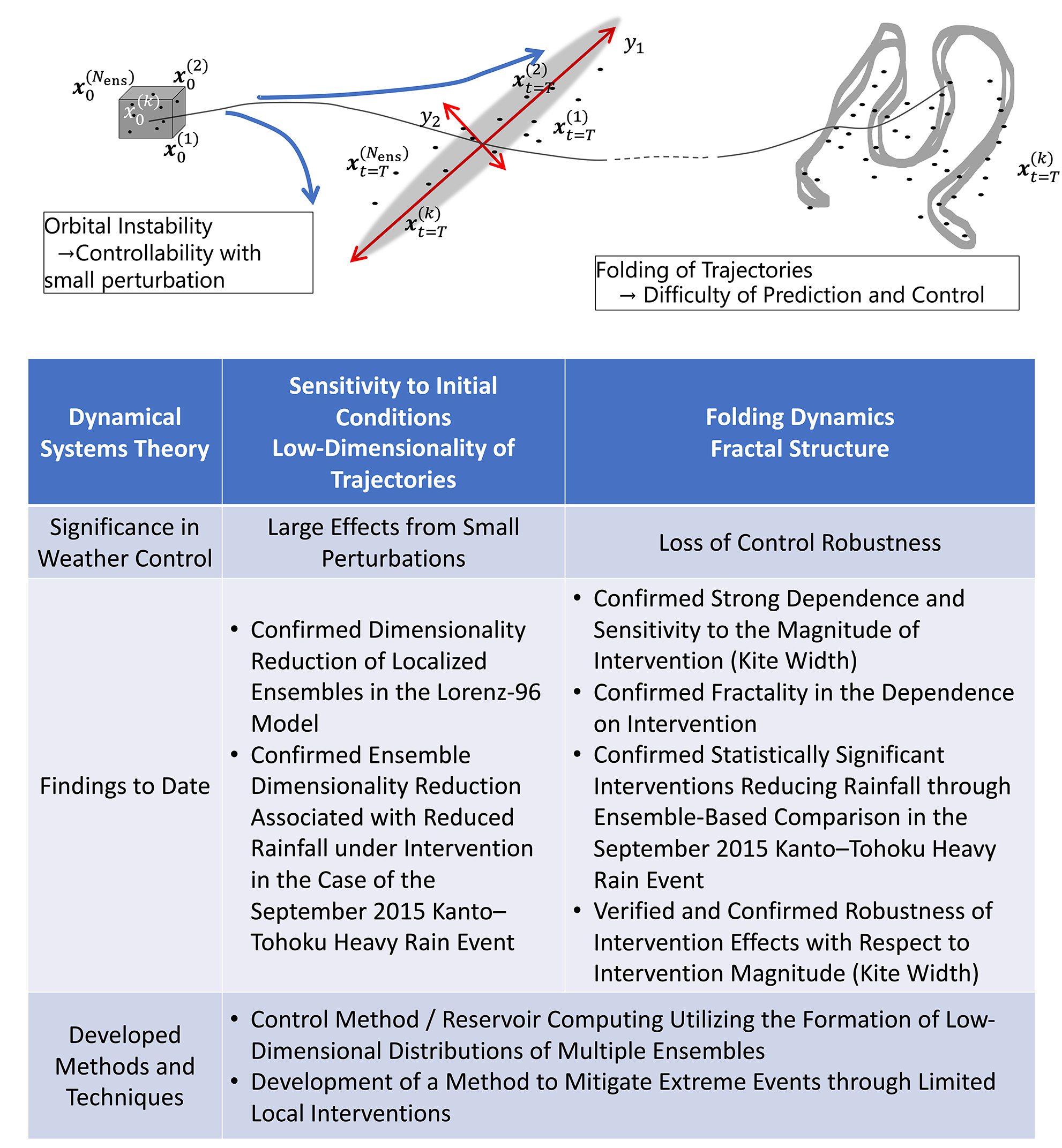

From the viewpoint of dynamical systems, the instability of orbits and sensitivity to initial conditions—features that characterize chaotic systems—can be advantageous for control, in that small inputs can induce large responses.

It is natural to assume asymmetry in instability along an orbit, and the directions of instability are considered to be those along which control inputs can effectively alter the system’s behavior.

In contrast, inputs given along stable directions are unlikely to have meaningful effects, since perturbations in these directions will decay over time.

Let us consider, for example, an ensemble of analyzed states obtained by data assimilation (that is, an estimated distribution of the current system state) or an initial ensemble corresponding to possible artificial interventions for weather control (that is, a localized range from which the system state can start).

These ensembles are sets of initial conditions localized near the true orbit and are expected to stretch along unstable directions as time evolves.

The resulting transient ensemble distribution is therefore expected to exhibit an effectively low-dimensional structure.

This implies that the space reachable by practical control is low-dimensional, and consequently, the optimization of control should also take place in an effectively low-dimensional space.

We have confirmed through numerical experiments using the Lorenz-63 model and the SCALE (Scalable Computing for Advanced Library and Environment) atmospheric model that such localized ensembles evolve over time to form effectively low-dimensional structures due to orbital instability.

On the other hand, in chaotic dynamical systems, the folding of trajectories often generates fractal basin boundaries.

This indicates that the robustness of control outcomes may be lost in nonlinear systems, depending on the sensitivity to input perturbations.

In our numerical experiments using the SCALE model, we have actually observed such phenomena in meteorological simulations.

This finding suggests that such fractal boundary structures are critical issues that must be considered when designing weather-control strategies.

We also expect this issue to be inevitable in the control of many other nonlinear systems beyond meteorology.

As illustrated schematically, it is important to understand and characterize the processes involving orbital instability, dimensionality reduction, and fractal structures, and to develop control methods that can operate effectively under these conditions.

Through numerical experiments, we aim to accumulate knowledge and integrate engineering approaches such as reservoir computing, rare-event simulation, and data assimilation, to develop methods applicable to weather control.

Specifically, we are working on two directions: (1) developing control methods that exploit transient low-dimensional structures of ensembles in combination with reservoir computing, and (2) designing strategies for the control of extreme events through limited local interventions inspired by rare-event simulation.