Chaos may enhance expressivity in cerebellar granular layer

Authors: Keita Tokuda, Naoya Fujiwara, Akihito Sudo, Yuichi Katori

Published in: Neural Networks, Vol. 136, pp. 72–86 (2021)

Award: 2022 Japanese Neural Network Society (JNNS) Best Paper Award

This study proposes a hypothesis that chaotic dynamics may enhance the expressivity of information representation in the cerebellar granular layer. The granular layer, which receives mossy fiber inputs from precerebellar nuclei such as the pontine nucleus, functions as the input stage of the cerebellum. In humans, this layer contains tens of billions of granule cells — accounting for the vast majority of neurons in the brain — and has long been considered a key site for neural computation.

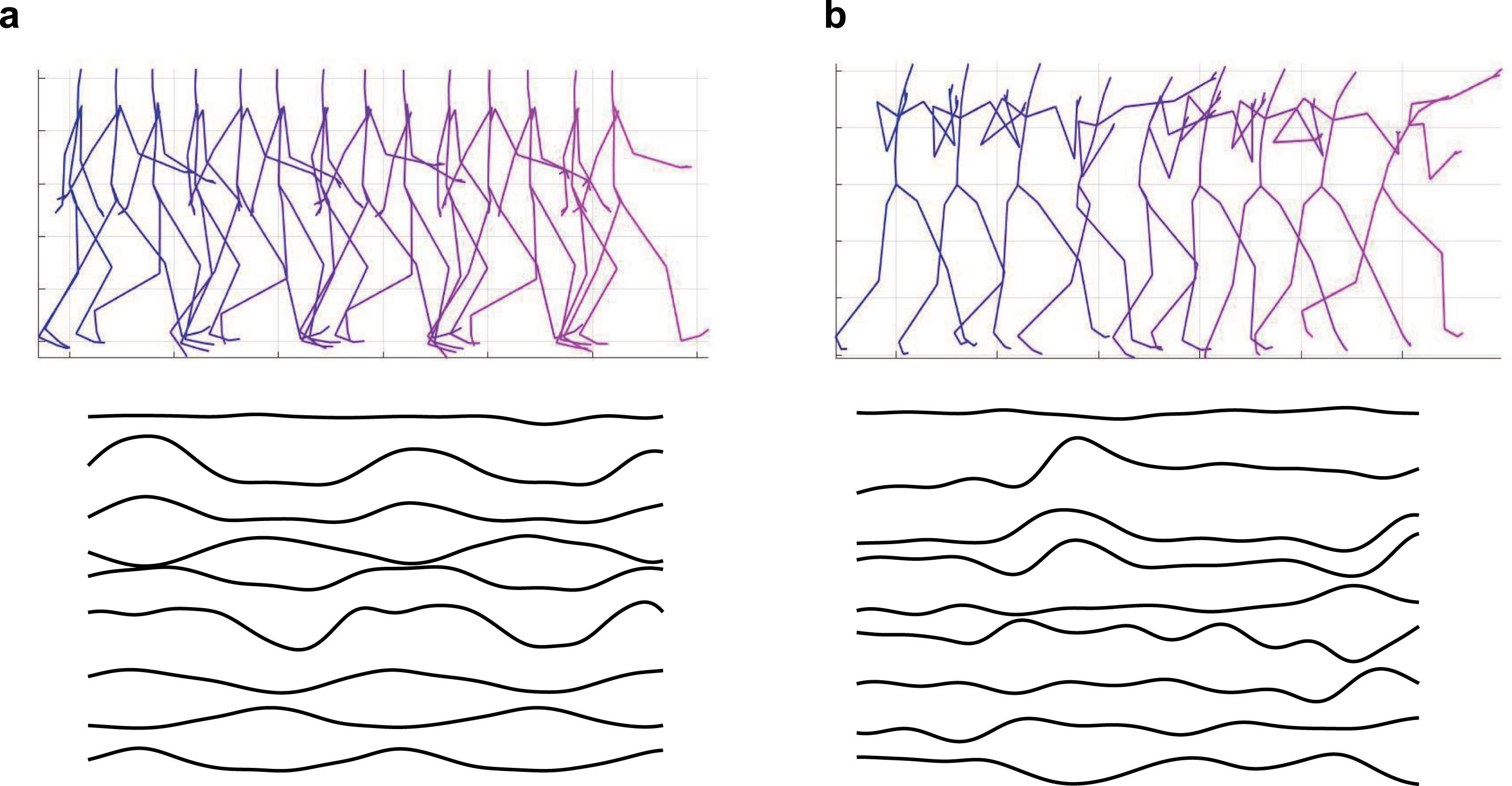

The cerebellum is known to play a critical role in generating precisely timed movements. Studies using cerebellum-dependent learning paradigms, such as classical eyeblink conditioning, have revealed that the cerebellum produces specific motor outputs with accurate temporal relationships to sensory stimuli1). It has been suggested that granule cells contribute to this function by exhibiting activity patterns that reflect the elapsed time after an input stimulus. In other words, different subsets of granule cells become active at specific delays following a sensory input, thereby representing the passage of time.

This temporal encoding has been modeled as emerging from the recurrent interactions between excitatory granule cells and inhibitory Golgi cells, which form a feedback network. Such recurrent architectures have been theorized to generate nonlinear dynamics that produce time-dependent firing patterns2). Building on this view, Yamazaki and Tanaka proposed that the cerebellum could be understood as a liquid state machine — a form of reservoir computing network capable of rich temporal processing3).

The idea for this study was inspired by the work of Vervaeke et al., who demonstrated that Golgi cells in the cerebellar granular layer are densely interconnected via gap junctions. Surprisingly, rather than promoting synchronization, these electrical connections can induce desynchronization between neighboring cells4). This finding recalled earlier theoretical studies by Tsuda and colleagues, who showed that gap-junction coupling can give rise to chaotic dynamics in neural systems5).

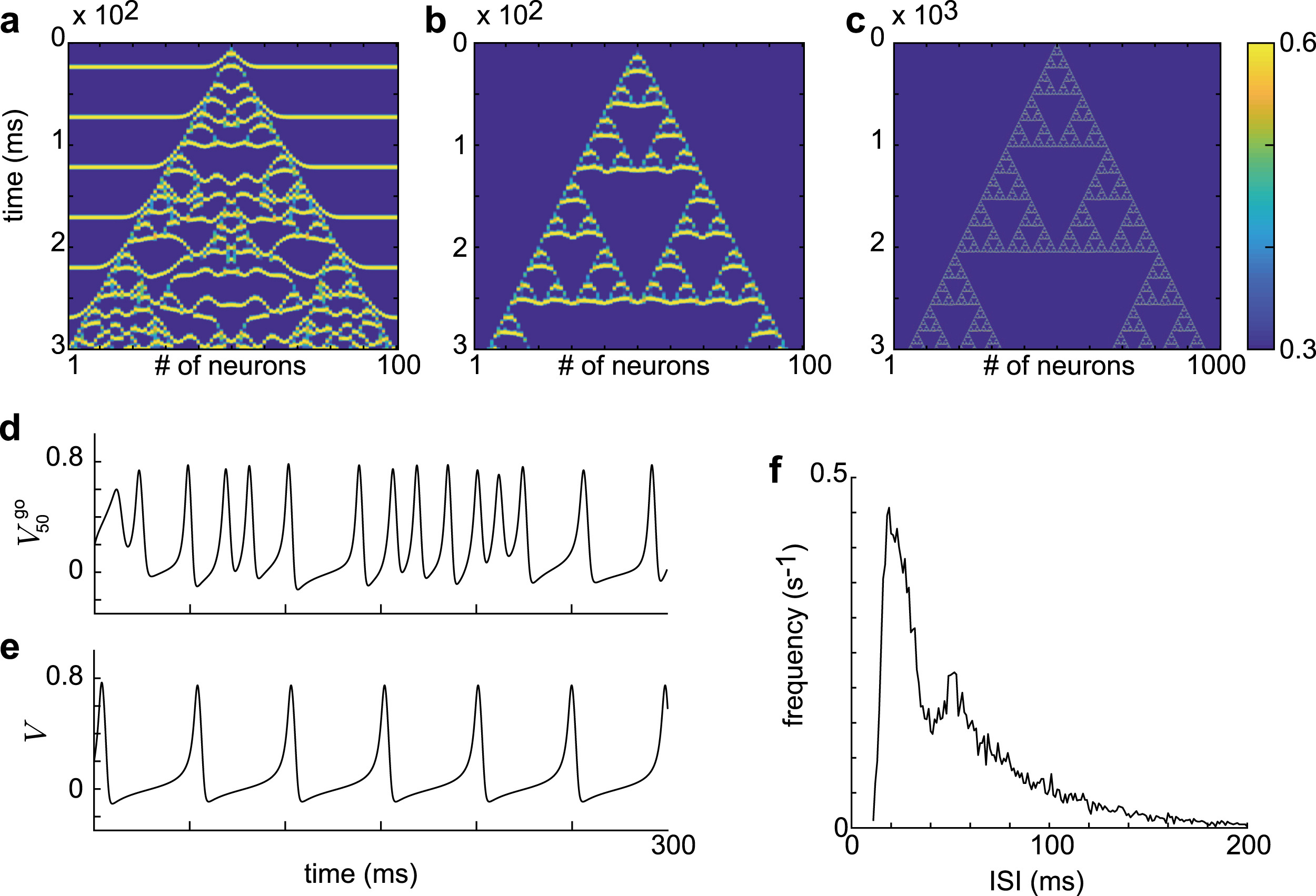

Motivated by these insights, we developed a computational model of the cerebellar granular layer in which Golgi cells interact through gap-junction-mediated coupling that induces chaos. Using the framework of reservoir computing, the model’s ability to generate time-specific activity patterns and diverse temporal outputs was quantitatively evaluated. The analysis revealed a strong relationship between the degree of chaos — measured by Lyapunov exponents and Lyapunov dimension — and the network’s expressive capacity. These results suggest that chaos may enhance the cerebellum’s computational power by expanding its ability to represent complex temporal information.

References

- Thompson R. F. (2005). In search of memory traces. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 1–23.

- Buonomano, D. V., & Mauk, M. (1994). Neural network model of the cerebellum: Temporal discrimination and the timing of motor responses. Neural Computation, 6(1), 38–55.

- Yamazaki, T., & Tanaka, S. (2007). The cerebellum as a liquid state machine. Neural Networks, 20(3), 290–297.

- Vervaeke, K., Lorincz, A., Gleeson, P., Farinella, M., Nusser, Z., & Silver, R. A. (2010). Rapid desynchronization of an electrically coupled interneuron network with sparse excitatory synaptic input. Neuron, 67(3), 435–451.

- Tsuda, I., Fujii, H., Tadokoro, S., Yasuoka, T., & Yamaguti, Y. (2004). Chaotic itinerancy as a mechanism of irregular changes between synchronization and desynchronization in a neural network. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience, 3(2), 159–182.